September 13, 2013, 8:15 am

A local musical hero joins the professional symphonists for their season opening concert in Derry-Londonderry

![Barry Douglas]()

Relatively fresh off his success with

At Sixes And Sevens, Camerata Ireland's Barry Douglas finds himself

tinkling the ivories tonight during something more traditional; a world famous piano concerto composed by none other than Pyotr Il'yich Tchaikovsky.

Book-ended by the music of Johannes Brahms, the composition provides rich sounds, warm sights and welcome insights into the world of 19th century classical music for a moderately sizable Millennium Forum audience. The rather epic arrangement of string, woodwind, brass and percussion instruments around the grand piano on centre stage is a feast for the eyes in itself.

A fun treatment of four student drinking songs, aka Brahms' Academic Festival Overture, opens the night. Merrily topped by a rampaging, string-dominated opening, which raises thoughts of a troubled or troublesome youth running away from danger, is followed by triumphant brass and flowing strings. There are few truly audible harmonies yet, but one is struck by the consistency of the tempo and the surprising stateliness of the violin playing. Like a good witch waving her wand, conductor JoAnn Faletta comfortingly eases the orchestra into a soulful sea of synchronic sound. Both cellos and double basses lend themselves well to the Forum's acoustics in what on the whole is quite an impressive overture.

When it is time for the centerpiece of this grand affair to begin, Faletta becomes hidden from view as our eyes turn to Barry Douglas' hands, reflected in the piano itself. Though he seemingly struggles to adapt to the heady and passionate nature of the opening in the Tchaikovsky piece, he very quickly adjusts to the consistently varying pace in the composition, while all four sets of strings strum away in a quadriad.

By the time his piano gently dies out as gentle string-playing leads us into the first movement proper, Douglas has everyone enraptured. The tension-filled and tonally varied Ukrainian folk slant of the first movement is the perfect test for Douglas' reflexes, and he is up to the task, sweat pouring from his head as he encloses himself in pure and absolute concentration. He is confident enough by now that the bipolar boundaries of the piece, reminiscent of a rippling brook one moment and thunderstorms the next, appear to pose little or no problem for him.

One is always fascinated by his sharpness, speed and skill, particularly in the very Clair De Lune-esque second movement. If Douglas' presence slightly overshadows the orchestra's efforts, with the exclusion of a rather sweet flute solo, it is no fault of Faletta and the instrumentalists, who are keeping up with him every step of the way.

The restless, breathless lyrical melody of the finale brings the piece to a tremendous conclusion, and when Douglas, Faletta and the orchestra stand up to prolonged applause, you know they've earned it.

Difficult though it is for Faletta and the musicians, barring Douglas, to match what we've just heard with Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, they do a commendable job. If it lacks the power of Tchaikovsky and the dominant piano, the symphony is remarkable in many ways, beginning with a rather Godfather-ly opening that leads the way for virtuous violins and numerous overlapping harmonies. As such, Faletta is forced into a slightly more controlling style of conducting while retaining her trust in the orchestra’s ability.

The middle of the first movement, laced with darkness, symbolizes a troublesome, tentative then heroic march, with gentler and more charming second and third movements preceding a strong finale. Highlighted by speedy cello plucking, woodwinds and a sensual string symphony, this composition brings the evening to a confident conclusion for Faletta and the orchestra. The applause is long and loud, reflecting a job well done by everyone involved.

The Ulster Orchestra will perform their grand opening concert featuring Barry Douglas in Belfast tonight at the Ulster Hall. For more information, check out their official site at www.ulsterorchestra.com.

↧

September 17, 2013, 10:37 am

The Derry-Londonderry troubadour's successful debut album is defined by versatility, experimentation and feeling

I can still remember watching Our Krypton Son in action for the first time. His seemingly perpetually sorrowful expression never seemed to deter him as he strummed away at a series of catchy acoustic chords in Derry-Londonderry's Cafe Nervosa some three years ago. Now, I didn't hear him for long - but what I heard was impressive enough to be remembered. This guy, I thought, has the right attitude. He can go places.

Sure enough, Our Krypton Son, or Chris McConaghy if you prefer to use his actual name, has commanded a sizeable following, the attention of Smalltown America Records and perhaps most importantly, a full band. With all that in tow, he's crafted a mighty fine debut album.

McConaghy's stylistic command is clearly evident in opening number "When I First Lay Dreaming". The thumping of drums and the strumming of guitars give way to wistful, David Bowie-esque vocals that, despite being drowned out a little by the rich instrumentals, are remarkably assured. While not quite as strong musically, the mood-lifting "Ill Wind" is catchier and more exuberant. Its upbeat, folky tone, defined by the mid song banjo solo, is the first sign of the varied experimentation that, in many ways, defines this record.

"Gargantuan", his most promising single to date, successfully combines the positives of the first two tracks, albeit with marginally more prominent beats. It's finger-clickin' good... if there were any nerves present earlier in the recording, they've been stripped away by now.

Contrary to its title, "Season In Hell" features a return to folky jollity and an exceptionally catchy riff or two. When one shares the struggle to escape that is evident in the lyrics, it is easy to understand why McConaghy has approached the song in this way. Struggles then take a backseat to understated bliss in "Catalonian Love Song", where you almost certainly sense that the songwriter visited one of the most beautiful cities in the world – Barcelona, in this case – and was inspired to write the dreamiest vocals and most memorable bell-driven riff he could think of. One only feels disappointment as bells, guitar and vocals quietly die out to be replaced by the prolonged sound of a closing drum beat; it's the sort of song you don't want to hear end.

While not quite as idealistic, or possibly enduring, the acoustically driven "Sunlight In The Ashes" is just as relaxing, and more musically rounded to boot. A tune that could belong in any era, it raises the irony that McConaghy signed with Smalltown America, because this is a song that literally wouldn't sound out of place in a small town in America. If the backing vocals are a little too echoey, at least McConaghy remains inventive.

"Birds On The Skylight" is McConaghy at his most poetic, sidestepping cheesiness to provide a dependable chronicle of powerlessness; by now, this Krypton Son has established himself as a fluid musical storyteller. Along with the drifty "Twitch", it's as close to his roots as he will come on this record, the reflective lyrics and rather old school arrangements of both songs essentially speaking to the needs of the "common man" in the North west of Ireland.

A rather brief, but gentle, detour into Mumford & Sons territory follows with "This Jealous Heart", before McConaghy signs off with the piano driven ballads "I'll Never Learn To Say Goodbye" and "Plutonium". Equally as heartfelt and genuine as one another, these songs cap off the record by successfully capturing what most independent artists strive to capture on their debut albums; the expressive and relatable clarity of the joy and pain in their own life experiences. Or, as McConaghy himself would put it, "memory, time, love, death, work, jealousy - the usual sh*t really."

↧

↧

September 20, 2013, 10:47 am

An old favourite returns to Derry-Londonderry - and it's as funny, grounded and professionally performed as ever

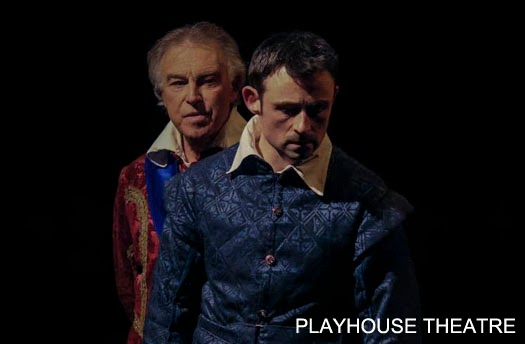

With nearly nine months as the City Of Culture 2013 theatre producer of Derry-Londonderry's Playhouse behind him, Kieran Griffiths decides to have some fun by bringing back an old favourite.

And what fun he has too.

Seven years ago, this reviewer saw Griffiths and his ageless cast-mates, Alan Wright, Michelle Forbes and Jude Cornett, take on Joe DiPietro and Jimmy Roberts' riotous musical comedy on the exact same stage. Today, these actors do much more than simply play their numerous roles; they inhabit them.

Griffiths' hands on, no holds barred directorial approach is the perfect fit for I Love You, You're Perfect, Now Change, a unique pop-cultural pastiche of extremely high and low satirical art that amuses, bemuses and delights all at once.

I Love You... is less a straightforward story than a series of distinctive sketches and vignettes about love, marriage, sex and relationships. Each sketch is amusingly introduced by three cue-card carrying local girls (Caoimhe Convery, Dearbhaile McKinney and Sinead Sharkey). And each scene features very different characters, moods and issues, allowing every cast member to be extremely expressive in what amounts a thinking person's comedic chronicle of the pros and cons of finding someone to spend your life with. Or not. It's Friends without benefits and boundaries, or Woody Allen with as few inhibitions as possible.

The laughs and messages come thick and fast amidst many catchy and sometimes affecting show tunes, be they about singledom, getting laid, one's first true love, one's last true love, marriage, parenthood or death.

Good vibrations spread all around the theater, even to musical director and pianist Maurice Kelly in between scenes – his reactions to the attention he receives from the "cue card girls" are rather priceless, just some of many memories one can take from this extremely enjoyable, grounded and professional production.

I Love You, You're Perfect, Now Change runs in Derry-Londonderry's Playhouse Theatre until Saturday September 21.

↧

September 25, 2013, 8:48 am

Haris Pasovic's production is spectacular, mind-blowing and sobering all at once

The audience stands on a hill, a little green hill not so far away, but well outside Derry-Londonderry's city walls. Directly opposite the doorway to the city's 2013 Venue, a saxophone, a cello, a boom, and the tinkling of bells are all heard. Part of a gloomy, Eastern European melody that gives you the first hint of where Haris Pasovic'

The Conquest Of Happiness is heading on the night of its world premiere, in and around Ebrington Square.

In a setting done up to resemble Palestine, we see a trio of young men kick a ball on a dusty road, while two women, mother and daughter – or is it aunt and niece? – get on with arts and crafts in their hut. To our left, the saxophonist (Rod McVey) and cellist (Neil Martin) play on. It is a triple-pronged multicultural contrast stretching from the West to the Middle East, with the sax adopting an Arabian slant of sorts by this stage. A former army barracks is a fitting stage for everyone here, trying to find peace and joy in three different parts of a war zone – as befits the title of the production, a conquest of happiness. Happiness, that is, in playing football, crafting a dress, finding new love or making music in dangerous surroundings. Such surroundings are emphasized when a modern-day digger, a symbol of Israeli aggression, destroys the hut and one of the boys fights the machine single-handedly.

It is here where we hear the voice of Bertrand Russell, whose pacifist writings inspired this production, for the first time. Played with remarkable low-key command by Cornelius Macarthy, Russell condemns the aggression in the previous scene as a thimbleful of recognizable audience members – who just so happen to include participants from the city's Codetta choir – melodiously join in the protest and lead us toward Ebrington Square.

What we have seen so far is a jolt to the senses, but it is only the proverbial warm up. Our feet sink into the shallow, gravelly ground of the square itself as we find ourselves surrounded by fortifications, vehicles, and several stages. This truly is a war zone.

Those who stare at the big stage in the centre of the square waiting for what will happen next don't immediately see what actually happens next... courageous speechmaking from activist Violeta – Mona Muratovic in one of many roles – in one corner, and the sound of "We Shall Overcome" ringing out in another. It can only be Bloody Sunday, and the drama is recreated soon after by a group running amongst us in the crowd. One flinches as the sound of a shot ringing out, and a man collapses, before Muratovic's spellbindingly staggering alto rendition of trad classic "She Moved Through The Fair" transforms shock into poignancy in what seems like a split second.

The show has barely begun, and the production team have already made a greater impact on our senses than most, if not all, cultural productions this year.

Macarthy as Russell makes another passionate statement before he joins several other actors in a genuinely spectacular Spanish tango on the centre stage. The setting being what it is, however – dictatorial Chile – ensures the excitement doesn't last long, and every dancer soon finds him or herself a prisoner at gunpoint. Amongst various brutal happenings, a young musician gets slowly beaten up in another sequence that skillfully depicts the fine line between the happiness bubbling on the surface and its much darker underbelly.

From Chile to Vietnam & Cambodia, as actions are largely replaced with language in a less physical, but no less powerful, sequence. The words of then US Secretary Of State Henry Kissinger, played boisterously by Shane O'Reilly, resonate against Russell's emotional power play – one argues that "the fortunate must not be strained in the exercise of pity over the unfortunate" while the other states that "the worship of money promotes... a death of character and purpose." Idealistic hippie views, from a US pair (deliberately?) resembling Greg and Marcia Brady, are aligned against a poor guitarist gunned down in a sea of mournful ballads, and later an American soldier's point of view.

That on its own would be enough for a comprehensive dramatic narrative on the East Asian War of the 1950's, 1960's and 1970's. But The Conquest Of Happiness digs deeper, with projected graphics of both Vietnam and Cambodia during the famous war and later Richard Nixon's speech in China appearing on the very walls of the Ebrington Square building. Cue silence, brief confusion, and several dancers, including Russell himself, appearing in casual clothing on centre stage, only to be dragged off one by one in a symbolization of the removal of resistance.

A sudden change in lighting, costumes, sound effects and tone of music takes us back three decades to World War II and life in the Jewish camps during the time of "The Final Solution". It is arguably here where the production is at its most emotionally draining; imagine a grittier Schindler's List. Nowhere is the sequence more hard hitting than when we watch Jews of all ages circle the enclosure and be herded out of sight on a truck with only sorrowful strings to accompany them. Why, a character asks, was "Ode To Joy" picked as the final song for Jewish children to sing before their likely termination? Why, indeed? Presenting victims with false hope, followed by guilty feelings of shame from the mouth of Russell himself, is as cruel as it gets. War has "made it impossible" for Russell to "live in a world of abstraction", and further sequences set in Bosnia, Rwanda (in the 1990's) and the Middle East (in the present day) solidify his point, reminding us that the West will not always positively intervene. Joyous choral flourishes, like Ladarice's "Yugoslavia", an undeniable highlight, are only brief respites.

Like us, Russell has seen cities "collapse and sink", and wonders if the world we live in is a "product... of febrile nightmares", yet he retains belief that there is light at the end of this extremely dark and harrowing tunnel, leading us out from the square and into the pleasant backdrop of the city and the Peace Bridge. As Macarthy and the rest of the talented cast lead us in a happy singalong, one realises that this sobering, immersive and interactive experience has amounted to much more than just about anyone could have expected it to – a unforgettable theatrical triumph of epic proportions.

The Conquest Of Happiness

will tour to Mostar Bridge, Ljubljana and Novi Sad before returning to Northern Ireland on October 25 and October 26 during the Belfast Festival at Queens. For more information, check out www.conquestofhappiness.com.

↧

September 26, 2013, 11:17 am

"Electrifying" title track is the highlight of a hugely innovative and interesting recording

It is uncharacteristic for the cello to be much more than a backing or background instrument (or a hindrance-turned-benefit, if you're

Timothy Dalton's James Bond), but Dungannon's Alana Henderson has taken it to the forefront in her four-track debut EP,

Wax & Wane.

And the first thing you notice about her brand of "cello pop" is the studious thoughtfulness that has gone into her compositions. Four minutes into the EP and she's a mistress of her craft, with a voice worthy of Joni Mitchell nestling alongside bitterly poetic lyrics and inventive string melodies.

The title track is a summation of the reflective nature of the whole recording, a series of alternately fragile or weary refrains fading into innovative vocal harmonies - the generally warm warbling of a once smitten, later bitten but now extremely well-written woman. It’s electrifying, and enough to make the whole EP worth purchasing by itself, but Henderson has much more to offer us.

Bookended by Irish Trad fiddling from Laura Wilkie, "The Tower" ingeniously mixes a foot-stomping groove with a cautionary tale of lost love, the need for familial support and rebuilding one's life. It isn't quite as multi-dimensional as the song that precedes it, but its titillating bluesiness still gets under your skin.

Now, imagine if Kate Nash or Ellie Goulding played string instruments on a regular basis, and you'd have "Song About A Song", arguably the most personal tune on the record. After hearing both this and the last song on the EP, "Two Turtle Doves", it becomes why Henderson has successfully collaborated with dreamily indie Belfast ensemble The Jepettos, her style and approach lending itself perfectly to their sensibilities.

By the time we hear Henderson's dulcet, soulful tones fade out for the last time, one senses that this end is only the beginning for this hugely promising young artist.

Listen to and purchase Wax & Wane at Bandcamp.

↧

↧

September 27, 2013, 7:18 am

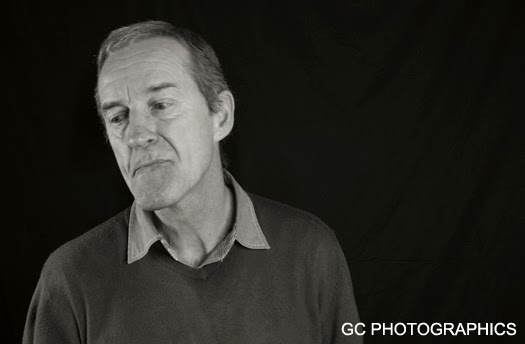

A comic, enlightening and hugely satisfying exploration of a famous Derry-Londonderry playwright

![]()

A soothingly downbeat cello melody is faintly heard as the audience search for their seats in Derry-Londonderry's Waterside Theatre. To the right of a large, fully draped white curtain in the centre of a rustic and minimalist set sits a washerwoman at work, with only the slightest flicker of candlelight to help. She appears so annoyed by the lack of light and atmosphere in her setting that she immediately resorts to taking a swig of ale from the mug beside her. Or perhaps she just needs a break.

The "washerwoman" in question is actually actress Kate O'Rourke, getting into character as Mistress Kempe, the active, buxom landlady of truly LegenDerry playwright George Farquhar. For the uninitiated, Farquhar is one of the best known and loved playwrights to come from the island of Ireland, his invaluable contributions to restoration comedy having endured for over three centuries.

By Mr Farquhar, written by Lindsay Sedgwick and directed by Caroline Byrne, is one of a series of theatrical events from Jonathan Burgess's Blue Eagle Theatre Company dedicated to celebrating the life and work of the famous playwright over a two week period.

The play is set in 1706, shortly before Farquhar's death. When we first see Farquhar, played with deceptively sly apathy by local actor and Farquhar fanatic Stephen Bradley, he wears an unsettling smirk that suggests he is not to be taken at face value. His ragged clothing and hangdog face suggest an almost stereotypical image of the struggling playwright, a man who is not basking in glory from the inspiration his plays are giving to early eighteenth century Londoners.

Feeling like "an animal of immense and hairy proportions", his self-pitying soliloquies to the audience depict the depression he allegedly feels over both estrangement from his wife and daughters and the struggle to finish his final play. Or is he hoodwinking us? For on one hand, he thinks the working title of his "comic masterpiece" literally "stinks" and briefly holds up a quill with a shrug, as if to say "why bother"? But on the other hand, there are moments where he joyfully sings and boasts about successfully completed the outline of the play. Bradley's depiction of Farquhar's varying moods make for great comic value, but initially, it is hard to care very much about the man.

Enter landlady and Mrs. Lovett soundalike Mistress Kempe, and the immediate fear that these two will have a Sweeney Todd dynamic, with the lady's love for the man inspiring him to continue and/or finish his work against the odds. Thankfully, By Mr Farquhar is no Shakespeare In Love. Here, Farquhar's inspiration comes not merely from the lady herself, but from absolutely everything that happens both in and around him during the remainder of the play.

O'Rourke plays Kempe as a tough nut to crack. She is the sort who will not be condescended to, despite being made to wait on Farquhar at every opportunity. In other words, she is a heavyweight of a presence, but to Farquhar, is she a paperweight, a makeweight or a weight on his shoulder? This is explored compellingly through the depiction of Kempe's role as a servant and as both an ear and an aid for the playwright's words.

By now, the play is freely alternating between Farquharian monologue and periodical dialogue between the two cast members, showing the male "hero" up as a desperately determined writer who seems no longer able to draw the line between theatre and real life in his work. He discusses what being in an auditorium feels like. He references Shakespeare and, in a rather anachronistic turn, Billy Joel ("And so it goes..."). He talks to Kempe about the possibility of getting closer to her, but, being married, she angrily knocks him back. He even goes as far as putting his feet in a pot of urine in what feels squirm-worthy to us, but enlightening to him.

Even more enlightening, for both Farquhar and the audience, is the Derry bard’s realization that he has "put too much of himself" into the play, according to Kempe. For the first time, she cracks a pleasant smile. And so do we, knowing that Farquhar will have to dig a little deeper to finish his "masterpiece". It is how he does it that enthralls us.

One still does not quite sympathize fully with him over the loss of his father and mother, as Bradley's portrayal and the tone of the play have been a little too laid back up to this point. But the lessons he learns, about heritage, marriage and parenthood, are appreciated. By reminiscing, and confiding in Kempe, he reawakens to his significance as a playwright and as a responsible parent. As he carves a doll for one of his daughters, and the strains of "Danny Boy" are heard offstage, The Beaux' Stratagem is born.

And, as the playwright falls victim to tuberculosis and is forced to fight even harder to finish his play (a telling reminder of how working so hard can ruin one's health), a genuinely caring bond between Farquhar and Kempe finally envelops. Bradley and O'Rourke work extremely hard to convey the strengthening emotions they feel both towards their work and one another.

By Mr Farquhar ends on a hugely satisfying note, with the playwright apparently letting his demons rest, acknowledging his inspirations, and leaving to enjoy the finished production and possibly a drink with his landlady. One might argue that it is a cheat to at last fully connect with Farquhar and Kempe just as they are leaving the stage, but it is actually the perfect ending to the play. For we have liked them all along; it just took ninety minutes for us to discover their emotional warmth. And perhaps that, in itself, is the central appeal of Farquhar's writing.

By Mr Farquhar is running at Derry-Londonderry's Waterside Theatre until Saturday September 29 as part of Blue Eagle's George Farquhar Theatre Festival.

↧

October 10, 2013, 9:48 am

Derry-Londonderry's Glassworks hosts a powerful, poetic story of punishing passion

If asked to sum up Darren Murphy's

Bunny's Vendetta in one word, I'd say that it's a mess. But it's a glorious mess. Murphy, director Caitriona McLaughlin and a gifted cast of actors and musicians have concocted a tale of music, murder and mystifying mirth right under an old church roof, a grand, garbled gospel of shocking surprise and strange satisfaction.

Set in 1950s Soho, and adapted loosely from George Farquhar's "Adventures Of Covent Garden",

Bunny's Vendetta is abound with analogies and symbolism before it has even begun.

For the wooden boards that adorn the back of the Glassworks suggest far more than a record producer's office wall. We are in a church, after all, and you sense that if the boards could be organ pipes, they would be. Maybe the producer is unhappy that his latest protege's own pipes have turned to wood, and it will take a recording session to spark him into life again. Or perhaps the producer is just being driven up the wall.

He's not alone. The play opens and closes with the sound of "John The Revelator", a clear reference to the confusion and later the potential inherent in central character Johnny Blade, played by Charlie Archer. Flat on the mat – that is to say, the very centre of the Glassworks, with a "recording studio" on one side and the "producer's office" on the other - Johnny is a wreck. His trousers are literally down and he has only Jessica Symonds' femme fatale Emelia Vamp (geddit?) and camp German studio man Hans (John "not the football legend" Giles) for company. In Hans' words, Johnny and Emelia are like Tristan & Isolde, with one promising another "the world" in a vision that he set out to complete, but never did.

The concept of the play is as uncertain as Johnny is at this stage. The Monotones' genuinely good music, a blend of The Rolling Stones and Johnny Cash, drowns out dialogue that verges on trite. The overt symbolism in the character names feels a little stereotypical, leaving the show to get by on humour that is sometimes Pythonesque, but at other times very Carry On.

Enter the seemingly insignificant Ricky (Cary Crankson), looking like a cross between Rick Astley and Roger Daltrey. Johnny has entrusted him with finding the lyrics for his latest song, so it does seem that he is going to play the part of the apparently insignificant patsy in Johnny's success. Elsewhere, Johnny and Emelia argue over the part this former "child star", the literal Vamp could play in the next recording. Drummer Gonzo (Jack Bence) taps a rhythm to their discussion while Hans observes with a series of intricate mannerisms. You admire everything that's going on, but you don't quite know where to focus. All the same, the effects of the play are being felt by both cast and audience on a very cinematically intimate set.

Johnny's meeting with producer Bunny Savage (yes, it's symbolic), played by Gerard McDermott, is striking in itself, a skin-crawling yet revealing discussion of the apathy, cruelty and single-mindedness in the music business. Think Lord Sugar crossed with Del Boy plus an uneasy level of savagery (of course) and innuendo. Sensing how intense the audience may feel, Murphy and McLaughlin correctly throw in an unexpected but catchy musical interlude featuring Bunny on harmonica, with acoustics and a washboard to back him up.

It's an all too brief respite before Emelia successfully seduces a tune out of Stitch (Howard Teale), a gifted writer with the appearance and backbone of Fredo Corleone. She has, as you might expect, stitched him up, but Johnny doesn't know this. Cue fireworks of the not necessarily pleasant kind when Johnny actually sees them together.

With the majority of the plot complications taken care of, writer, director and cast are more focused in Act Two. They successfully wrap every story element around the most Farquharian element of the show – finishing and performing a work of art in complicated circumstances.

Along the way, there is a painful encounter between Bunny and Ricky, Emelia learning the difference between reciting a song and inhabiting it, Johnny unexpectedly rediscovering both his bearings and his true talent through a musical bond with Emelia, and shocking revelations that spell a bittersweet – strike that, bitter – and darkly punishing fate for nearly every character involved.

It all packs a passionate and rather tragically poetic punch, with Johnny indeed becoming a "Revelator"– just not in the way he surely intended.

↧

October 15, 2013, 11:08 am

Musicians from both sides of the province light up Derry-Londonderry's Millennium Forum, paying homage to a singing and songwriting legend along the way

He was the "missing Beatle" and John Lennon's favourite American artist. Yet Harry Nilsson, who passed away nearly two decades ago, is at once one of the most celebrated yet overlooked voices in modern music. For all his song writing gifts, his two biggest hits were covers, and when one thinks of "Coconut", he or she will be more likely to associate it with The Muppets or Quentin Tarantino's

Reservoir Dogs.

The Millennium Forum stage is therefore set for dreadlocked Belfast troubadour Peter "Duke Special" Wilson to remind us of Nilsson's finest credentials and to give us a good evening's worth of musical entertainment in his own right.

The disappointingly moderate but nonetheless expectant Forum audience are initially greeted by Wilson's "special guest", Derry-Londonderry pianist Meadbh McGinley, and her Steinway piano. And they are not to be let down. McGinley, who entered the local musical spotlight during her city's successful City Of Culture campaign in 2010, has come along in leaps and bounds since.

She projects a varyingly precise pitch that echoes Alannah Myles one minute and Adele the next, her graceful and sturdy piano playing carefully reflecting a poise that alternates between haunting humanity and absolute concentration. It's an ear-markedly elegant performance.

As the Harry Nilsson tribute begins, the red-tied, smiling Peter Wilson is to be joined by a not entirely familiar backing band. Guitarist Paul Pilot is still present, but gone are usual suspects Temperance Society Chip Bailey and Ben Castle. In their place are drummer Stephen Leacock (formerly of General Fiasco), and, most strikingly, trombonist, violinist & co-vocalist Hannah Peel. The fine-tuned sultriness of this Craigavon-born femme vocale is the perfect fit for Wilson's vaudevillian style.

To be frank, tonight any tune, Nilsson or otherwise, is a near perfect fit for Wilson. It has become Wilson's wont over the years to exhibit his surrealness, subtle or obvious, through the prism of genuinely good music. This is already obvious in "Me And My Arrow" which owes a minor debt to "Yellow Submarine" and "Turn On Your Radio", where Wilson's voice sounds exceptionally echoey. Or is that more down to the Forum's acoustics? Either way, the effect is positive.

Solitary then becomes sublime as an intimate performance of "One", made famous by Aimee Mann in Magnolia, precedes the long-awaited "Coconut". The popular song presents the best and the worst of this concert in a matter of minutes; while Wilson’s rendition, featuring shivering strings from Peel, is inspiringly jazzy, the atmosphere feels a little too formal and restrictive for maximum enjoyment. Nevertheless, the interactivity in the final refrain goes down pretty well with everyone in the Forum.

As does "Without You". All memories of Mariah Carey's depressingly memorable nineties cover of said song are successfully wiped away in the tonal equivalent of a lower-key "Freewheel". Peel bobs her head entrancingly from side to side while Wilson gently glides his fingers over the piano. Even if Wilson and Peel's one key vocal duet is a little awkward, that is a minor problem.

After placating the fan base with a few of his own tunes, including an audibly exhausting but quietly soothing performance of "No Cover Up" and a slightly restrained “Salvation Tambourine”, Wilson and his ensemble mark their return to Nilsson with a handful of tunes more suited to the surroundings. There remains enough variation here and there to end the evening on a very high note, notably, a solo performance from Peel ("Don’t Leave Me"), the thumping groove of "Beehive State", and, of course, "Everybody’s Talkin'", made famous by Midnight Cowboy. No one seems to care if Wilson struggles a tiny bit on the highest note of that well-known song. Such has been the quiet captivation in Harry Nilsson's – and Duke Special's, and Meadbh McGinley's – musical prowess.

Duke Special's "Harry Nilsson" tour will continue throughout Ireland until November 20, with Duke returning to Belfast at the Empire on December 6. For more information, check out www.dukespecial.com. For more on Meadbh McGinley, check her out on Facebook.

↧

October 19, 2013, 5:05 am

A spectacular solo acting showcase lights up the Waterside Theatre stage in Derry-Londonderry

William Shakespeare's

The Rape of Lucrece, brought to the City of Culture 2013 by the Royal Shakespeare Company after a successful public and critical reception in Edinburgh, Dublin and beyond, is a textbook example of how theatre literally

is performance.

It's arguably even better as an illustration of how a little time and contemplation can put all things, particularly works of art, in their proper place. A tragic, two-hour Elizabethan English poem about death, rape and violence does not feel like instantly appealing source material for any modern stage. The wordiness can seem excessive, the scenario off-putting. But on reflection, director Elizabeth Freestone's production is more than simply words. It's a distinctive collage of music, motion and monologues highlighted by a sparkling central performance from actress and singer Camille O’Sullivan.

Either side of the seventy-five minute, one act play, O'Sullivan is bubbly and bouncy, fully acknowledging the presence and efforts of Derry-born co-collaborator Feargal Murray on piano and the appreciation of her audience. Within the seventy-five minutes, O’Sullivan's concentration is pure and absolute as she projects a whole gamut of emotions through three "costumes", two speaking voices, one singing voice and a countless range of expressions.

The Rape Of Lucrece draws on the Roman legend of Lucretia, whose rape and subsequent suicide led to revolt and laid the foundations for the Roman Republic in the sixth century BC. The Roman names are abbreviated in the poem, with Lucretia becoming Lucrece and her husband Tarquinius, son of the King Of Rome, becoming Tarquin. And in an innovative move, both are played by O'Sullivan.

Initially, O'Sullivan is cold and deceptively reserved, like you would expect rape perpetrator Tarquin to be. The actress, dressed in a long black coat and with her hair tied back, strongly enunciates in a sometimes forceful, sometimes raspy voice which ensures that the texture of the language and nuance of her performance gently enrich our senses.

In another innovative move, large parts of the play are sung, through compositions that echo Ennio Morricone, Bob Dylan, the gothic vulnerability of Shakespears Sister (coincidence?) and even ABBA. With a singing voice worthy of Etta James, O'Sullivan confidently strides around the stage like a dominant giantess, an Irish Marion Cotillard. She inhabits both her characters' souls and ours.

Particularly arresting is O'Sullivan's depiction of Lucrece's vulnerability. When she removes her coat and lets her hair down in a manner echoing Scarlett Johansson in Girl With A Pearl Earring and lies down on the stage floor in a white dress, her theatrical nakedness is there for all to see. As Lucrece, her tears are real and her passionate physical presence is extremely heartfelt. Like a rock concert, but without all the frivolity and superficiality, she hits you like a thunderbolt and never lets go of your attention.

The final third of the play sees O'Sullivan depict the consequences of Tarquin's immorality to us. Contemplation, regret, sorrowful singing and mournful monologuing imbue the actress's characterizations in a haunting finale worthy of everything that has come before. A piece of classical art has been given a new lease of life by both the RSC and a remarkably talented actress - and everyone in the Waterside Theatre knows it.

The Rape Of Lucrece runs at Derry-Londonderry's Waterside Theatre until October 20. For more information, click here.

↧

↧

October 23, 2013, 3:02 am

The UK's most prestigious art exhibition visits Derry-Londonderry. Our writer tours the four galleries and presents his initial thoughts

Leaving the relatively shiny cobblestones of the now nearly two-year-old Ebrington Square behind me, I tread onto a short twisting gravel passage sandwiched between mossy surfaces. Lest I sound too poetic or artistic, the brick building in front of me looks relatively ordinary; worn-down and old-fashioned, as you'd expect from a site that ceased to be an army barracks a long time ago. But wait a minute. Twisting and turning everyday life or run-of-the-mill objects into art that makes a powerful statement; isn't that what the Turner Prize is all about?

The inside of the building is as professionally prepared as you would expect any "prestigious" art house to be. Programmes and art books are easily accessible in the reception area. Legenderry coffee, tea and food, prepared by the staff from the city's most famous Warehouse, await upstairs for those needing to take a breather.

Into prize nominee David Shrigley's exhibition I step, and before even looking at the artwork (more on this in a moment) I am struck by the spotlessness of the gallery's walls and floor, the lighting and the London accented voices I hear. It is as if one has been instantaneously transported to England's capital city.

![The Turner Prize 2013]() But back to Shrigley. Renowned for drawings and animations that satirise and commentate on what people do and say, the Macclesfield-born artist has chosen 2012's "Life Model" as the basis for his exhibit. And what do we have here? A tall, mechanical and nude humanoid figure, with rather large ears, a long nose, a prominent fringe and very, very thick sideburns.

But back to Shrigley. Renowned for drawings and animations that satirise and commentate on what people do and say, the Macclesfield-born artist has chosen 2012's "Life Model" as the basis for his exhibit. And what do we have here? A tall, mechanical and nude humanoid figure, with rather large ears, a long nose, a prominent fringe and very, very thick sideburns.

"He" even blinks at inconsistent intervals, and "urinates" in a metal bucket placed below him. On its own, the model seems rather creepy, suggesting a man "going about his business" with absolutely no awareness of his appearance to others. The black humour that Shrigley's work has been praised for comes to the fore here.

The true "joy" in this exhibit, however, lies in its interactivity. Various visitors are invited to draw or paint their own artistic impressions of the mechanical model, and each impression is exhibited on the walls of the gallery for everyone to see. One visitor thinks that the sculpture looks like "your man from Lord Of The Rings" (Gollum, surely?), one visitor thinks the art is "more Andy Warhol than Shrigley", and one visitor writes, beside his own drawing of the model, that "his fig leaf fell off".

Levity, cultural references, and matters of fact, all on the same wall. Analytical and artistic minds working hand in hand through the eyes of their beholders. It would appear that both Shrigley and his audience have completely grasped the message of the Turner Prize.

Laure Prouvost has earned her reputation through films and installations with a richly layered, fractured narrative, disorienting stories with surreal interruptions. Perhaps it is no surprise, then, that I find her unconventional storytelling, in the "Wantee" and "Grandma's Dream" films, to be a little baffling – muddled videos in wildly different but strangely comfortable surroundings. Yet because of that, it is distinctive.

"Wantee" is displayed within a collection of empty chairs and empty tables in a dark room. It's like Amelie minus the excessive colour and quirk. "Grandma's Dream" can be watched on a soft carpeted floor, in a tiny pink enclosure that reminds one of an attic with light and without all the dust and clutter.

The films themselves inspire actions and reactions through bizarre imagery – one such image that springs to mind is a teapot attached to the back of a passenger jet – and excellent sound. When "Grandma" sinks into muddy water, and when a piece of paper is scrunched up, you really sense it happening.

![The Turner Prize 2013]() A conflicting spectrum of emotions awaits us in another darkened room, the gallery where the paintings of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye lie. There is a narrative connection between the six paintings, with expressions, features and actions of the solitary figure (or two, as is the case with "The Generosity") in each painting saying more than a detailed background ever could.

A conflicting spectrum of emotions awaits us in another darkened room, the gallery where the paintings of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye lie. There is a narrative connection between the six paintings, with expressions, features and actions of the solitary figure (or two, as is the case with "The Generosity") in each painting saying more than a detailed background ever could.

Opposite "The Generosity", which appears to imply two men struggling to survive in a very tough scenario, lies a painting of what appears to be a soldier in battle. Perhaps there is a war theme here. Not too far away from the starkly untrustworthy smile of "Bound Over To Keep The Faith" rests another painting of a genuinely happy man. I also see a portrait of a man relaxing contentedly on a beach, and another with a man staring into the distance, as if he does not quite know what to do.

It is the very lack of a background, in addition to the emphasis on specific features – the eyes, teeth and socks stand out in this darkened room – that makes these images as interesting and open to interpretation as they are.

All sorts of interpretations can be taken from Tino Sehgal's exhibition, which isn't really "art" in the expected sense of the word at all. When we think of art, we often align it with painting, drawing, music, dance and so on, things that titillate the eyes and ears of the beholder. Sehgal focuses on the brain of the beholder. Two words, in this case, "market economy", are presented to the visitor by an attendant. It is then left for the visitor to have as detailed a discussion about the aforementioned two words with the attendant as he or she possibly can.

Whether questioner or answerer agree with one another or not is irrelevant – the whole exhibition is about formulating a stimulating discussion, filling one’s head with ideas, and improving one's way of thinking. It's a remarkable idea – Brain Training without imagery. Like every other exhibition in this year's Turner Prize, it defines not only the artist's individuality but the visitor's individuality, one of four galleries that merges the thoughts, dreams and fears of the populace into a not always cohesive, but satisfying, whole.

The Turner Prize 2013 will be staged in Derry-Londonderry's Ebrington Barracks from October 23 2013 (today) to January 5 2014. The winner will be announced at an awards ceremony at Ebrington on Monday December 2. For more information, visit www.turnerprize2013.org.

↧

October 26, 2013, 4:16 am

A full house bears witness to “one of the most treasured cultural happenings” in Derry-Londonderry

Numerous memorable musical extravaganzas such as Sons & Daughters, Music City and the Fleadh have helped to cement the City Of Culture 2013's reputation as a "City Of Song"; and the city's inaugural International Choral Festival stands poised to enhance it. A cavalcade of cosmopolitan choirs have descended upon Derry-Londonderry for the first time, and we won't be forgetting their impact in a hurry.

In the words of tonight's presenter, Mark Patterson, we are set for "one of the most treasured cultural happenings" in the city. The question is: Does the

City Songs concert, regarded as central to the success of the festival, live up to its billing?

The omens are good. The opening gala concert the night before has been, by all accounts, a phenomenal success, translating into a full house in an incandescently lit St. Columb's Theatre.

Enter Latvian Voices, seven Eastern European young ladies in multi-cultural attire. The style of their clothing is reflected in the tone of their singing early on – impressive but inconsistent. I am initially impressed by their range and chemistry, but yet to be truly absorbed.

Fortunately, these seven girls soon earn their corn and deserved applause through an eclectic mix of traditional and modern folk, laden with multiple octave singing, rippling tempos, ear-piercing vocal solos and human beat-boxing.

"Gloria" and "Sanctus" are highly commendable; think Mozart's "Requiem" with a relaxing jazzy beat and Lakme's "Flower Duet" on top. But they save their best 'til the end, notably a spine-tingling rendition of "Danny Boy", arranged by Latvian composer Ēriks Ešenvalds, and a version of the U2 classic "I Still Haven't Found What I’m Looking For" (listen below) that ought to have even Bono eating his heart out.

It's enough for a good evening's entertainment. Yet when choirs start gathering around the audience following the interval, we know that we've only been served the appetizer before the main course.

That being, City Songs, a newly commissioned work by Ešenvalds, Australian poet Emma Jones and British artist Imogen Heap, which sees six choirs come together with the Orchestra of Ireland for a musical narrative based in a city "upon a hill".

It could be any city, but the descriptions within the piece fit Derry-Londonderry to a tee. Harmony after harmony adorns the theatre of St. Columba as the Holst Singers, Codetta, the Roundhouse Choir, Encore Contemporary Choir and Colmcille Ladies slowly make their way to join the Music Promise Junior Choir on stage. It's like Music City in a music hall.

Conductor Stephen Layton, a fundamental presence, enunciates in Radio DJ speak, signifying the beginning of our narrative. A young traveller – Heap – enters a city at dawn, listening to the radio ("The Radio") and looking for her childhood home. City history is explored through a series of distinctive contrasts, with Heap’s broken and vulnerable improvisation alongside the Music Promise Choir’s optimistic depiction of a village becoming a city, a small city becoming huge, possibly even a burgeoning choir becoming great ("The City")... a pattern is starting to emerge.

Through interacting with the Roundhouse Choir ("Workers"), the Holst Singers ("Pedestrians") and poetry from Emma Jones, Heap relays to us the difficulty of finding one’s way in a city, while the choirs around her musically transmit the situations and personalities of differing citizens to the audience. "Buskers" goes one step further, with not only Heap's vocals impressing but also the thematic richness of the composition itself. The struggle, nature, wisdom and talent of street singers are delivered in a clear and pleasant manner by the Colmcille Ladies. Shades of Paul Muldoon and Mark Anthony Turnage's "At Sixes And Sevens" are evident here.

Donal Doherty’s Codetta Choir get their chance to excel in "Voices" and "Customers", the latter featuring a standout solo from Helen O'Hare. Here, the traveller follows the tune of an ice-cream truck to find a way home; it is intriguing how much poetry can be drawn from the sight, sound and food of such a familiar vehicle.

The careful structure of the piece, which allows all choirs and especially Heap to fully express themselves, continues right up to the finale, through the happiness of "Commuters", the moody, dreamy "The City (Night)" and a rumination on homecoming, "Road Motet", where the traveller concludes that sometimes the journey is better than the arrival. With the quality of the singing and instrumentals stellar throughout, it is best to focus on the tone of the piece and how it relates to the narrative; and it relates extremely well.

When the spectacular opening rhythm of "Radio" repeats itself in the joyful "Parade", Derry-Londonderry unites in song as singers wash around the spectators again, the vocals slowly fading into the closing, solitary and melancholic prose of Heap. As regretful as her final monologue sounds, it is clear that she and her character never felt alone; and on a night awash with talent, neither did we.

The inaugural City Of Derry International Choral Festival runs until Sunday October 27. For more information, visit www.codichoral.com.

↧

November 7, 2013, 10:29 am

The City Of Culture's specially commissioned punk musical provides no end of Glee for its Rebels Without A Cause – but not necessarily for its audience

When you title a production

Teenage Kicks, you're in danger of digging a hole for yourself before the show has even begun. One knows that Colin Bateman's musical, staged in Derry-Londonderry’s Millennium Forum and co-produced by the Forum and Nerve Centre, will not be able to avoid the inevitable comparisons with the song that made The Undertones, and its beautifully simplistic summation of the spirit behind the 1970s punk movement. Not to mention the record store and label that injected said song into the stratosphere to begin with.

So, how to go about things? Retell the story through the prism of a powerful central performance, a la

Good Vibrations, or go for the appeal of an ensemble jukebox musical?

Ultimately, Bateman takes aim for the middle ground and ends up with something more Phil Collins than Undertones; that is to say, anvilicious messages and not entirely convincing "love" stories layered over undeniably commendable production values. As Collins himself would say, how can something so right, at least aesthetically, end up going so wrong? Something happens on the way to (punk) heaven during the show, to be sure, but it's not all that exciting. That, surely, is not what the producers intended.

The central story involves Derry teen Jimmy McMurphy (Drew Dillon) and his escape from Northern Ireland in 1981, by way of a student exchange programme to St. Francis Xavier High School in Iowa, USA. Principal Truman (Hugh McLaughlin) expects a war-torn refugee, but the exuberant, rock-loving youngster has something else up his sleeve for his new friends – the "rebellion" and "anarchy" of the Irish punk scene.

It’s a framework around which the production scatters a total of twelve punk classics (including, but not limited to, Stiff Little Fingers'"Alternative Ulster" and Wreckless Eric's "Whole Wide World") and the efforts of the ensemble to set the material alight, culminating in a group performance of The Undertones' most famous song at the end of each act.

If it sounds like nothing new, it's because it frankly isn't. Early on, the intentionally sloppy choreography and not quite in unison singing hints that maybe the play will be more about the passion than the music, a collection of young, confused voices finding their way in an adult world – but how many times have we heard this before?

And what follows? An Irish guy forced over to America in clichéd circumstances (a gun going off in a struggle) where he introduces a class of kids to the wonders of punk? Dangerous echoes of the White Man's Burden abound. I suppose we should be grateful, at least, that Jimmy's background is genuinely seeped in Irish punk and that he isn't teaching the Chuck Berry's of the 1980's how to rock and roll.

It's not impossible to do something exciting with these tropes; the cast of Bend It Like Beckham and 2004's Wimbledon had enough charm and energy to gloss over those films' predictability. But even the economically inventive set design (among the best I've seen this year), the consummate skill of the backing band and the likable earnestness of the cast of all ages can't rescue Bateman's script.

Gifted with a host of talent to work with, Bateman wastes it. It isn't hard to imagine what Teenage Kicks might be with a more courageous, not to mention clear, vision. One recalls Nicky Harley as the geeky Melissa; refreshingly refusing to be patronised, or adhere to the ugly duckling-turned-swan stereotype, she breaks clear to convincingly relay the differences between Irish and American culture (isn't it fascinating how many Americans delightfully embrace their "Irishness", especially today?) in addition to criticizing the music that the production openly worships.

In addition to Harley, Hugh McLaughlin delivers a nicely executed comic performance worthy of Greg Davies, Karen Rush and Rhiannon Chesterman are convincingly vulnerable as a troubled mother and daughter, respectively, and Drew Dillon and Darren Franklin (as Jimmy's cousin, Kevin) are solid leads. But the cast's attempts to form any sort of chemistry on stage never stretch beyond friendship. It becomes clear that the true romance in Teenage Kicks lies not between the boys, girls, men and women of Derry and Iowa, but between Colin Bateman and the music he loves.

Yet behind the exciting tunes and a sprinkling of amusing moments lies a troublesome, thoughtful message; that the punk of the 1970s wasn't so much about rebellion but about creating a new clique of Rebels Without A Cause, who sensed that there was something more to life but were no more certain about how to go about it. That Northern Ireland's legendary contribution to the musical world may have been no edgier than the Graduates and Breakfast Clubs of this world; as much as we loved them, and still do, they reek of conservatism underneath their subversive blankets. In short, Teenage Kicks is really only intriguing in spite of itself. It's a punk Glee or Alternative Ulster's Mamma Mia; and if that's what you want, then that's what you'll get. Although given both its status and the people involved, I feel one has a right to expect more.

Teenage Kicks runs in Derry-Londonderry's Millennium Forum until Saturday November 9. For more information, click here.

↧

November 20, 2013, 3:54 am

Derry-Londonderry hosts a turbulent tale of two types of love conquering all... or trying to

British playwright Helen Edmundson penned

The Clearing amidst the "horror" and "disbelief" in Europeans' expressions throughout the barbarism of the civil war in the former Yugoslavia. Her theory was that in similar circumstances, there was no way we absolutely could not be susceptible to the influence of propaganda or, in her words, "fall prey to the lust for revenge and absolute supremacy".

Edmunson, however, refuses to believe that the dream of a world where people "have their lives for themselves" is no more than a dream; and, inspired by the "phoenix from the flames" theme partly inherent in the inaugural City Of Culture year, Derry-Londonderry's Playhouse Theatre have re-commissioned

The Clearing for a contemporary audience.

When the play opens, in 1652 Ireland, Cromwellian England is in the process of solving the "Irish Question" as only it thinks it can; by eradicating the entire population in a genocidal movement involving fighting, plagues and famine. By 1653, The Act Of Transplantation is in full force; the Irish Nationalists who have not been killed or shipped off to colonies in the Americas are set for Connacht, then the poorest and most inhospitable region in Ireland.

Not that young English Protestant Robert Preston (Kieran Griffiths) and his Irish wife Madeleine (Megan Armitage, in what is surely a star-making turn) are too perturbed by all of this; they and their baby son live happily in the Emerald Isle amongst friends from both sides of the religious divide. Those familiar with Joan Lingard’s literature will tie Robert and Madeleine's situation in with a seventeenth century Across The Barricades– a young couple overcoming, or trying to overcome, serious political and spiritual issues in a strange time where, as Robert puts it, people "aren't themselves" and "have forgotten how to smile".

Still, a smile seems fixed on the free-spirited Madeleine's glowing visage a lot of the time, especially when she is around the cynical Pierce (6Degrees' Seamus O'Hara) and her "spiritual sister", Killaine (Doireann McKenna). She has no hesitation in naming Killaine her child’s godmother, despite the troubled times, for "fine English ladies have their companions", and Killaine is her companion. That word will take on deeper meaning as The Clearing goes on.

For the play doesn't open in a spooky, Blair Witch-esque wood for no reason. When Robert realises that his friend Solomon (Peter Hudson) and Solomon’s outspoken wife Susaneh (a fiery Judith Burnett) have not been faithful to the Commonwealth, the cracks in our patriotic central character’s determinedly confident facade start to show. He is persuaded to be more careful by the bullish Governor Sturnam (the excellent Les Clark) and advised to focus on "the world" rather than "life and longing" in a country that "cannot be trusted". These fears do not transmit to Madeleine, however, raising the first of a number of major and timeless issues in the play – should one compromise on the things he or she truly believes in?

This shift in focus spreads to Susaneh, who no longer believes she can make friends in this mistrustful atmosphere. Hate turns her bitter, and she and Solomon, along with Pierce, Killaine and even Madeleine to an extent, become a metaphor – for animals, unsafe, in a clearing, in a wood. They are there to be discarded, or eaten away when the hierarchy has no use for them.

From building on this, the play becomes an entirely different beast in its second half. By the end of Act One, Pierce is reluctant to hold Madeleine's son as the baby is not of his blood, but by Act Two's end, he feels closer to Madeleine than ever, and she him. Why is this?

The capture of Killaine by British soldiers and the forced transplantation of Solomon and Susaneh virtually turns the production on its head. Madeleine's hitherto suppressed brotherly feelings for Pierce, and affection for Killaine, are now at the forefront along with Robert's true priorities. We wonder now if Madeleine truly loves Robert, or if she is in a marriage of convenience, for stability's sake.

Helen Edmunson, director Patricia Kessler, Kieran Griffiths and Megan Armitage deserve special praise for convincing us that this once apparently blissful union is really scarcely believable at its core. No matter how genuine Robert’s attachment to Madeleine is, his by-the-bookishness and her rebelliousness are always in danger of coming to blows in a politically charged atmosphere – which is precisely what happens in The Clearing, both in the play and the woods.

Armitage goes as far as threatening to turn the play into a one-woman show during Madeleine's ill-fated pursuit of Killaine. Her performance is equally humorous and heartbreaking, the highlight being a truly creepy dance in Sturnam’s office. In a rather bewitching manner, she convinces us that this obstructive bureaucrat might not really want to be all that obstructive after all. She is an "Irish" wife in every sense of the nationality – and don't Robert and the audience know it!

As with all Playhouse Productions, the minimalist sets give the well structured narrative and the whole ensemble room to thrive. And if The Clearing can at times be a little too broad in pronouncing its theses, it is the journey along the way, concluding with Robert and Madeleine’s final meeting of clarity, that matters. Perhaps, we find, many of our dreams may be realised after all, even if some gaps really are too great to be bridged.

↧

↧

November 22, 2013, 8:11 am

An alternately physical and psychological thriller opens Derry-Londonderry's Foyle Film Festival

A postmodern pastiche that has unsurprisingly made Quentin Tarantino proud, Aharon Keshales & Navot Papushado's

Big Bad Wolves is a lean, mean tale of torture, vengeance and black comedy merged into an immensely satisfying whole. It is likely to be as divisive as it is riveting; some will argue that it is no more than a thinly disguised combination of movie clichés, or that it exploits both its cast and narrative to justify nauseatingly virile violence. But it's really more of a worrying window into the worst excesses of differing cultures; a critique of stereotypical prejudices built around a triple-pronged story of characters driven by persistence and resentment, one that also manages to be funny and lively in the space of less than two hours.

From the start, camera angles, explosions of noise, images of worried children, and red herrings like mangled subtitles (yes, at least at the beginning) and a trail of coloured sweets in the woods are applied to heighten senses of mystery and dread in advance of meeting the "main" characters – simultaneously timid and creepy teacher Dror (an excellent Rotem Keinan), vigilante cop Miki (an almost equally good Lior Ashkenazi), and Gidi (Tzahi Grad).

The three men, fathers of only daughters, are all driven by bitterness. Miki, by the need to arrest the perpetrator of a series of murders in the town, despite protests from his superiors. Gidi, by the need to torture the man who tortured one of the murder victims: his own daughter. And Dror, by the need to escape suspicion after his repeated pleas for innocence have fallen on deaf ears.

To say much more about the plot would be spoiling everything the film has to offer: sometimes clichéd, although I'd like to believe the directors are subverting their tropes, and sometimes not. But what is worth examining here is what works so well and what doesn't.

What stands out, above all, is Rotem Keinan's acting. Dror walks such a fine line between normality and queasiness – and that’s just his expressions! – that you’re always uneasy whenever he’s on screen, no matter how many times he claims he didn't "do it".

Torture sequences, alternately psychological, physical and even humorous, channel early Tarantino while managing to stretch the boundaries of squeamishness and say something. There's a notable scene where Miki tries to convince Gidi that if you torture someone for long enough, he'll admit any "truth" just to stop you torturing him (spoiler: in Dror's case, Miki is right) and another where Gidi points out that if you want a "maniac", which he believes Dror is, to tell the truth, you've got to be equally maniacal towards him.

The danger of falling for the "sympathy card" is also raised in a conversation between Dror and Miki while Gidi bakes a cake to the sound of Buddy Holly's "Every Day". It's as "Stuck In The Middle With You" as Big Bad Wolves gets, and with the unexpected arrival of Gidi's father, the film twists and turns into even more unexpected territory.

It's unfortunate that odd pieces of overdone schlock (the testing of a sound proof room, an in-your-face torture of a small dog) or virtually superfluous characters (a man on a horse) creep into view, while female characters are almost entirely sidelined. Some may also complain, not unjustly so, that large sections of the film are a little too theatrical. Consider these necessary in the context of Big Bad Wolves, however, and you are likely to be rewarded with a gripping and intimate thriller, with final shots that are sure to leave you more than a little shaken and stirred.

Big Bad Wolves opened the 26th annual Foyle Film Festival. For more information on the festival itself, check out www.foylefilmfestival.org.

↧

November 26, 2013, 2:45 pm

A well acted, tightly plotted chronicle of the adaptation of Mary Poppins is let down by middlebrow frivolity and condescension

Films about the creation process of much loved film adaptations always have it tough, I think, because of how close we hold them to our heart. It is because of this that even if an adapted film went through development hell, might have been worse than the source material and possibly even angered the author, one cannot help but root for both the film to exist and the author to approve it in the end. After all, it won us over, so why shouldn't it win over the author too?

Saving Mr Banks, as well acted, tightly plotted and lushly presented it may be, falls foul of this malaise. Using a dual layered narrative that takes place in the 1900s and 1960s, respectively, it charts brief but significant spells in the life of PL Travers, played by Annie Buckley as an idealistic child and Emma Thompson as a cynical adult.

Having written the infamous Mary Poppins character as both vain and stern, Travers is understandably frightened by what Walt Disney (Tom Hanks) will do to Poppins on screen. Hence, even after two decades' worth of effort, she can't bear to grant him the rights. But Travers needs the money, and Disney is nothing if not persistent, making Travers' reluctant journey to Hollywood inevitable.

When she arrives in the USA, director John Lee Hancock (The Blind Side) regularly begins applying "human" flashbacks of Travers' youth alongside a "self-aware" chronicle of the film-making process, featuring the legendary Richard and Robert Sherman (Jason Schwartzman and B.J. Novak) and some of their equally legendary jingles. It is fun to watch, but creates a tone that is problematic; serious family drama meets bittersweet whimsy. Neither time period seems fully certain of itself.

One could easily surrender to the fantasy of the picture and the well-structured plot, but when Hancock wants us to take things more seriously, the film fails to fully convince. As Travers' alcoholic father and troubled mother, respectively, Colin Farrell and Ruth Wilson give their cardboard characters far more respect than they deserve. Similarly, Emma Thompson is so convincing as a cartoonish, closed off snob that the inevitable cracking of her facade, even to a point, isn't entirely believable. Only in the company of her chauffeur Ralph (Paul Giamatti) does the humanity genuinely come through.

Tom Hanks is another problem. Forget Disney's distribution of Saving Mr Banks for a moment – Hanks' presence all but guarantees that the slimy and crass aspects of Walt Disney will be whitewashed. Hanks just doesn't do slimy; it is inevitable that he will make Disney, for the most part, a familial and rather likable figure. It doesn't have to be this way; Colin Firth's George VI, Liam Neeson's Oskar Schindler and Jesse Eisenberg's Mark Zuckerberg were little or nothing like their real-life counterparts, but the actors inhabited their characters so well that they were able to create them in their own image in the context of the film. Because of the routine script and his personality, Hanks cannot quite do so, giving the whole production a slight uneasy feel.

And yet, when we hear about and understand how dear the characters in Mary Poppins are to PL Travers, the film works, albeit fleetingly, as a telling commentary about how easily we can get sucked in to picking holes in "crass", modern entertainment, while forgetting that the entertainments we hold so dear are imperfect themselves. Saving Mr Banks also reminds us how childhood can be both enriching and tarnishing at once, how a little "Disneyfication" can do no harm when applied properly, and how genuine achievements can emerge in spite of the potentially damaging effects of commercialisation. (Look at Finding Nemo.)

But even then, Saving Mr Banks cannot escape the middlebrow frivolity and condescension that permeates it, most evidently in the drawn out scene where Disney finally convinces Travers to sell him the rights. As one sits and watches Hanks-Disney try to help Thompson-Travers realise what's truly important for her, one cannot help but be reminded of four lines spoken by Dick Van Dyke to David Tomlinson in Mary Poppins itself:

"You've got to grind, grind, grind at that grindstone

Though child 'ood slips like sand through a sieve

And all too soon they've upped and grown and then they've flown

"And it's too late for you to give."

A far more brisk and elegant way of delivering a similar message that Saving Mr Banks (or should that be Saving Mrs Travers?) takes so long to get across. If only Hancock and the screenwriters had learned more of the right lessons from their chief inspiration.

↧

November 29, 2013, 4:37 am

The Oscar-winning director and local screenwriter open up to the Derry-Londonderry public in a warm and genial chat

By the time they take their seats in Derry-Londonderry's St. Columb's Hall, Danny Boyle and Frank Cottrell Boyce have been walking around the City Of Culture 2013 all day. It is believed that Boyce was asked for his photo more often than Boyle; either way, this duo seem tailor made for one another.

Having collaborated successfully in 2004's

Millions and, more notably, the opening ceremony for the 2012 Olympic Games, the high-profile pair are delighted to spill the beans in front of a simultaneously relaxed and expectant audience. Boyle, he of

Trainspotting and the Oscar-winning

Slumdog Millionaire, forms a warm and genial rapport with the crowd that spreads around the old hall and regularly inspires laughter and cheers.

"I've been in Derry(-Londonderry) many times", Boyle admits, "but the Peace Bridge has sort of passed me by!" What doesn't pass us by is his revelation that Trainspotting (watch a scene below) - in this writer's opinion, Boyle's best film and still an undoubted must watch - had its first ever public screening in Derry-Londonderry!

Allegedly, the audience was baffled, for as Boyle points out, sequels always score highest in test screenings. That, and it was deemed "a lost cause" to make a drug movie at the time, although the subsequent reviews ("Hollywood, come in please: your time is up"– Ian Nathan, EMPIRE) and box office surely quelled Boyle's fears.

The Lancashire-born director does not think that film is a reflective media, but that "its origin stems through working class culture". Hence action movies, to him, are the purest, for they "connect with the origins of film". But Boyle's 2002 zombie flick 28 Days Later went beyond that, for reasons unknown to even Boyle himself before filming.

"We thought it would be about social rage and loss of temperament”, he says. “But 9/11 transformed the film into a parable about the vulnerability of cities. Tangentially and entertainingly, it illustrates that the big cities aren't safe."

Frank Cottrell Boyce then recalls Tony Wilson, the late co-founder of Factory Records, and the inspiration he drew from both Wilson and news reports while writing his screenplay for 24 Hour Party People, in which Steve Coogan plays Wilson. Boyce says, “Wilson’s vision reeked of freedom. He said that you could either go away and make a great career for yourself, or stay at home and make it a better place.” Something that no doubt many who live in the City Of Culture 2013 would relate to.

While Boyle regrets not being able to attend the momentous Return Of Colmcille, conceived by Boyce, both men are delighted to discuss what Boyle considers his crowning achievement: the opening ceremony at London 2012. (Watch my favourite moment from said ceremony below, featuring Daniel "007" Craig and HM The Queen.)

"When devising London 2012, we thought: what is it that defines us, represents us? We're not that good at films, but we're great at music. And reproducing that kind of music (in front of everyone) is the defining representation of a nation. Everywhere has its own music."

"We could have got anyone to help us", Boyce adds, "but we kept loyal to our friends and to people we had worked with before."

But how on earth did Boyle, Boyce and their crew all raise their game for such a ceremony?

"You have to believe", says Boyle. "You have to believe that on some level, the work you do and the people you work with truly are the best there is. You take the job not because of the money, but because you believe in it. Look at Stevie Wonder and John Lennon; Wonder may have been a better musician, but Paul McCartney didn't do his best music with Wonder."

Of course, response was divisive. Giles Coren initially described the whole show as "Punk Rock Teletubbies", yet within a matter of minutes, according to Boyle, Coren believed it was the "greatest night of his life." Perhaps he acknowledged that Boyle had recognised what the event meant to people as a symbol, as a means of bringing people together.

Boyce backs Boyle up. "The footballer motivated by money ends up on the bench at Real Madrid, but the footballer who actually wants to play football ends up doing so much more." Some things are so much better for what they do than what they are; here, Boyce cites both London 2012 and David Shrigley's mechanical model at the Turner Prize.

As the Q & A begins, Boyle moves on to the intriguing topics of Millions (a "moving and fantastic" script that he only regrets not making as a musical) the sequel to Trainspotting (which he’ll consider doing with a “Whatever Happened To The Likely Lads?” tone) and his upcoming seven-part series for television, Babylon.

But the very mention of Millions has piqued my interest. Boyle is a director, after all, who was compared to Hitchcock and the Coen Brothers near the start of his career, and made a name for himself with quirky, grimy, “independent” work such as Shallow Grave and Trainspotting. What on earth caused the shift in tone in his filmography that led to more "family-friendly" and middlebrow fare like Millions and Slumdog Millionaire (watch the trailer above), I ask him?

"I saw Slumdog as another version of Millions. They were both films about a boy who loved money and a boy who understood it. Also, when we made The Beach, in Thailand, we were given everything we needed, and it didn't suit me. It made us behave very imperialistically. I couldn't profit from such a set up.

"So I thought that, when we were doing Slumdog, we'd make the film with a smaller cast in Mumbai. I learned that being beholden to where you're working is more important to you than money. Trust the city and it gives you back a sea of prosperity at the end."

He parts with some valuable words of wisdom for young filmmakers: "Cinema is about fresh, new blood. It needs you more than it needs us. Work with your peers, and you will find everything you need."

Which, in turn, leads us to think. Of what Lennon & McCartney, and what Boyle & Boyce, have achieved. And who would bet against the next truly significant filmic partnership emerging from this very city?

↧

December 3, 2013, 11:07 am

Neil Hannon & Thomas Walsh find themselves literally in the Limelight at the end of their ELO-inspired cricket punk tour – and they do not disappoint

"So now you know what happens in the studio when we're making these records."

Thus speaks Neil Hannon as the final night of the cricket collective that he and Thomas Walsh of Pugwash set up four years ago, The Duckworth Lewis Method, nears the end of its

Sticky Wickets tour.

It's not so much the wickets that have been sticky, however, as the floor of Belfast's Limelight, and Hannon references this in one of many not-even-cricket-related asides that Hannon, Walsh and their band will toss in on the night.

A night that, to me, can be summed up best as jiggery, pokery, trickery, jokery tomfoolery, going by the lyrics and tone of one of their most well-known tunes (listen above). As entertainers, Hannon & Walsh can deliver shows that amount to a nonsensical mess, but how exciting and energising they are.

The Duckworth Lewis Method's album covers look like they're all about cricket, and their songs could be perceived as being solely about cricket, but the band as a whole go way beyond cricket. Their ELO-inspired, vaudevillian punk transcends the appeal of a game not everyone – especially not this writer – fully understands. As promising as the earnest and rollicking melodies of support act The Statics are, they are mild-mannered by comparison.

Contemporary fads like Movember and the best (or worst) of celebrity gossip are slyly merged with a collection of tunes that range from joyously ridiculous to simply sublime. One is lost in the roars of delight that regularly emerge from all corners of the Limelight, throughout the hilarity of "The Laughing Cavaliers", the funky beat of "Boom Boom Afridi" and a handful of truly unexpected 1980s covers, to name but a few.

But we also marvel at how seamlessly both Hannon & Walsh tie in a well-known sport with everyday life and lovely melodies. "The Nightwatchman" and "Out In The Middle" are strong cases in point; the latter could be about a cricket fielder, but also about a man trapped at a metaphorical crossroads.

If asked about the evening, I'm sure Hannon & Walsh would say "It's Just Not Cricket", but really, It's Not Just Cricket. And it's all the better for it.

↧

↧

December 5, 2013, 6:06 am

Field Day Theatre Company return to Derry-Londonderry with a patchwork thunderbolt of human fear and emotionalism

Easy though it might be to pigeonhole Sam Shepard's